What is a Coin? Part 2.

What propels YOU in the work you do?

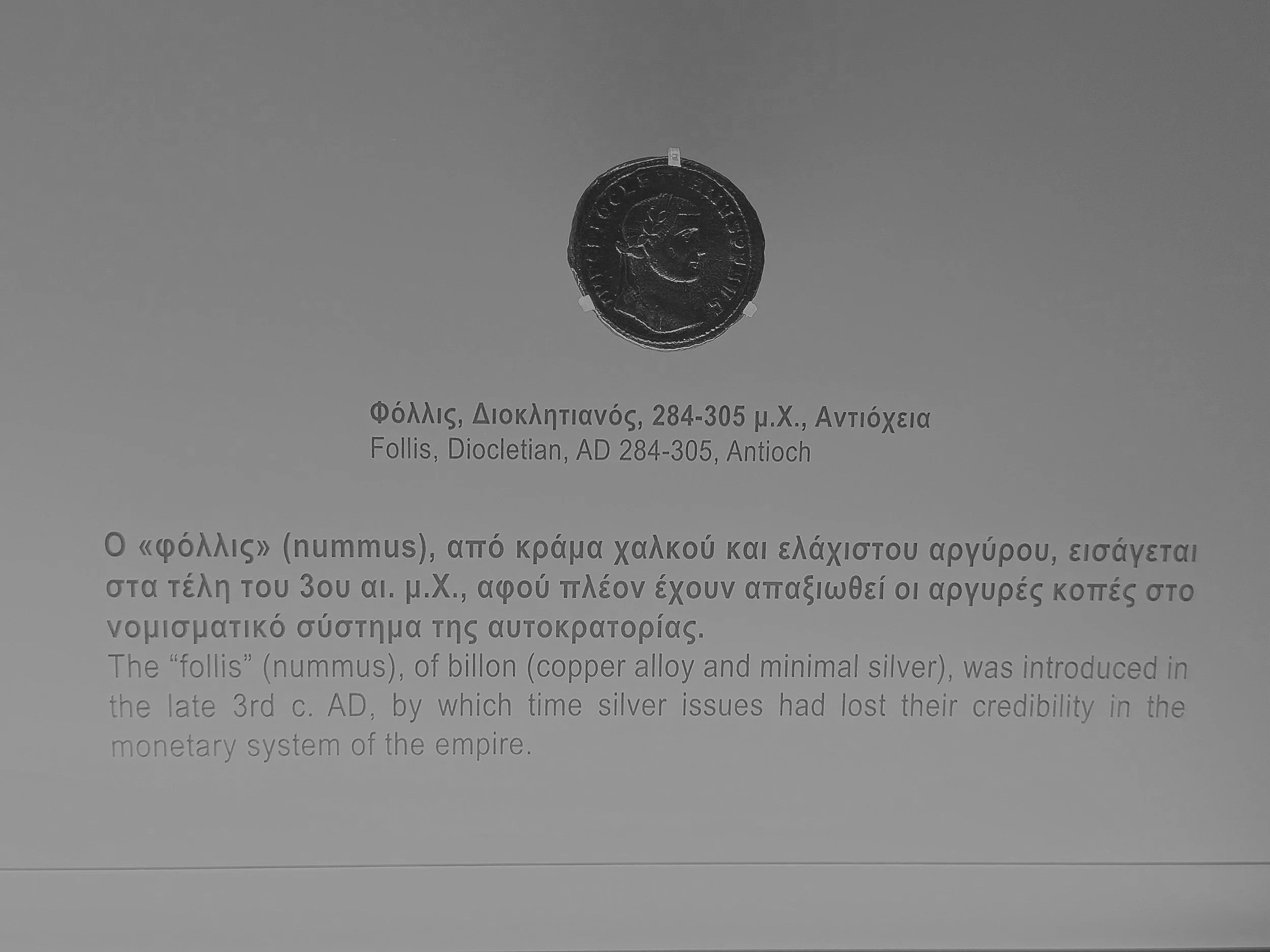

Numismatic Museum, Athens. 2024.

Today, I am loaded with meetings and I expect to get very little research done. However, it has been a productive week as the writing retreat from last week has rebooted my thoughts and I have been able to tackle a few overdue tasks. Over the past week I have focused on data-sharing, LOD (Linked Open Data), and OCR (Optical Character Recognition) to perform topic modelling. I am working on three independent but interrelated research projects. The first a project under the supervision of Dr. Shawn Graham (my supervisor) and his XLab group where we are, broadly speaking, reevaluating some older projects and reshaping them into a more user-friendly/accessible medium. I am honestly not sure how much I can speak about this at the moment.

The second is for the Unknown Ottawa project in which my reposibility is exploring and setting up more backend technical stuff that concerns inputting pre-contact and 19th century material culture data into a repository (Borealis) and getting this repository to talk to a public facing platform to provide open-access data of said material culture in collaboration with the local indigenous communities. The third is the Inhabiting Byzantine Athens project and though I have not done much direct work on this project lately, the work I am doing is helping to inform the research I am participating in.

What does this all have to do with “what is a coin?” and what drives my research? Well, the digital end, specifically the OCR and Topic Modelling, is meant to support my research on how the label ‘Byzantine’ evolved into everyday language to describe Roman Coins. The objective is to examine digitized manuscripts between the 16th and 19th centuries and convert them into plain text in order to identify key terms and their associations within the manuscripts. Topic Modelling is not novel, but is new to me. The goal is to produce some form of output that allows me to explore the impact the label ‘Byzantine’ has on the interpretation of Roman coins and the historical narratives created from their study. In essence, I am performing some form of digital-quasi-historiographical analysis of Byzantine numismatics, which informs my ideas on Wicked Byzantine Problems.

The question, “What propels you in the work you do?” arrived in my email this morning and will be asked in a workshop at Acadia University next week. It is slightly ominous as I have been wrestling with questions about my research's impact and relevance to the problems we face in our contemporary world. Problems that Schofield (2024) addresses in his book Wicked Problems for Archaeologists. So, why is my research important, relevant, and most importantly, needs to be open-access and public? To answer these questions, I’ve been exploring the question: What is a coin? And how our understanding of these metallic objects influences our sense of identity and knowledge of the world around us. Furthermore, how we relabel/rename coins, change their identities, or re-identify them, impacts our understanding of history. And in some ways forces us (Byzantinists) to rethink our approach to numismatics as we all proclaim “decolonization” but continue to use a very colonial/orientalist label that reshapes and manipulates history.

What propels you in the work you do?

I am not an ardent collector of coins, nor am I a numismatist in its purest sense, but what I am (and this may answer a small part of the above question) is a researcher who has identified a problem in a field that has significant impacts on the reception of a history that has for many years been misidentified and now has led us into a reckoning which presents us with wicked problems. I have argued, and continue to do so, that coins are perhaps the most fascinating and adaptable medium for engaging students with the ancient and medieval worlds. A coin’s dynamic life-cycle and durability lends itself to one of the very few objects from the ancient world that students and the public can touch, feel, see, and even smell all the while knowing that a person from one-thousand, two-thousand and even twenty-five hundred years ago touched, used, traded, wore and deposited. You are physically touching the past and contributing to a coin’s history. So, what propels me to do what I do? The students. Cliché? Maybe. But in an AI/social-media-obsessed world that continuously enforces the digital as a means to communicate and know our surrounding environment and history, a coin can go a long way to ground us and to reflect on the past.